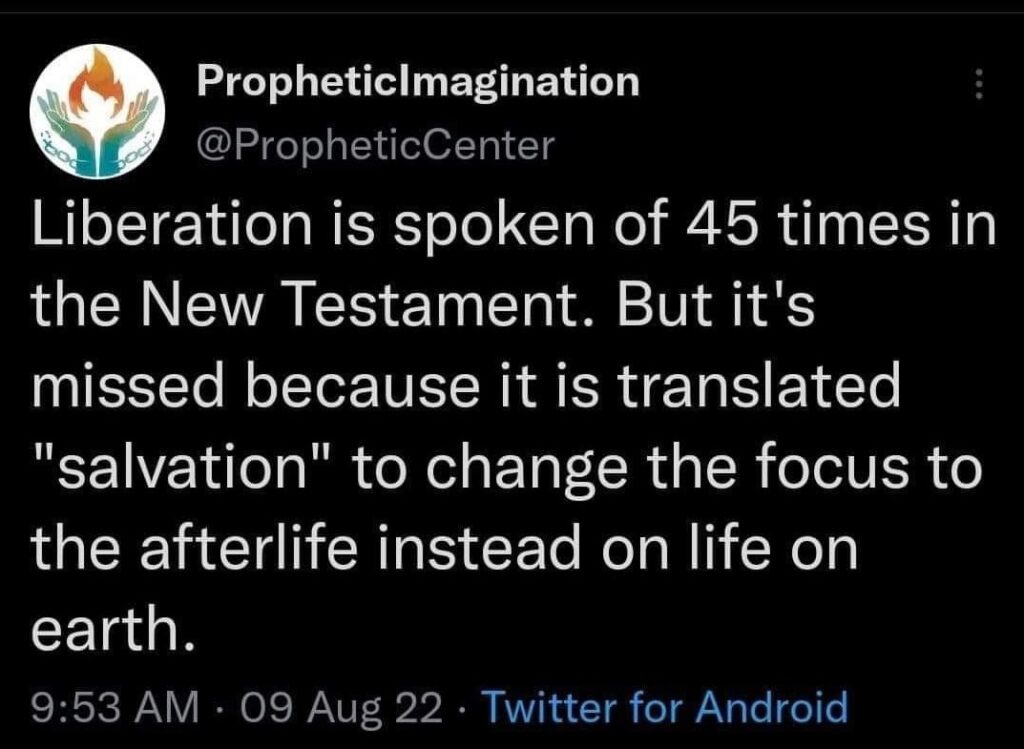

A few weeks ago, I made this tweet and it sparked a lot of debate. In some ways it was too simplistic, not every instance of “soteria” should be translated “liberation,” but that wasn’t the point. The point was to critique the way that our English translations use theologically saturated words that no longer reflect the original meaning.

The word “salvation,” although technically an accurate translation, has come to mean spiritual salvation from hell and is only occasionally used metaphorically for physical salvation. However, the use of “soteria” in the Bible is rarely (if ever) actually about the afterlife.

This is why I recommended “liberation” as I believe its meaning in today’s context more accurately reflects the political significance that the original writers were indicating. In many cases, both “liberation” and “salvation” could be used interchangeably, but when we read or hear them in a religious text, we bring all of our theological baggage with us.

It is not just the New Testament that we bring this baggage with us, it is also seen in the Old Testament. To give an example of this, I want to examine one verse, Psalm 51:14:

“Deliver me from the guilt of bloodshed, O God, you who are God my Savior, and my tongue will sing of your righteousness” (NIV).

Most other English translations are rather similar to this translation. A glimpse into an interlinear Bible might even indicate there is no question as to the translation. Their focus is pretty clear, the author is asking for forgiveness from bloodshed because God is righteous.

However, let’s look at an alternate translation:

“Rescue me from bloodshed, O’ God of my liberation, [then] my tongue will sing of your justice.”

Many of the words are synonyms, but there is a significant difference in the theological meaning of the words used. In one version, David (the cited author) is asking for forgiveness of the bloodshed he caused and the other is asking for protection from bloodshed.

Most of my life, I never really thought about the language being used. However, as I have become more interested in the philosophy of linguistics, I am starting to notice how often translations use saturated words to hold to certain theologies. This has caused me to look deeper at many texts like this one. What I found was, I believe, a misrepresentation of the text to maintain a spiritual focus instead of a physical focus.

For instance, the translation of “דָּם” seems to be significant in the two variations on the verse. If it does mean “guilt of bloodshed,” this would be the only time that it holds that meaning. All other times, it just means “blood” or “bloodshed.”

Christianity’s focus on the removal of guilt to achieve salvation in the afterlife has shaped the way that we understand the language of the Bible, even if the passage is not addressing the issue of guilt.

So, why translate this as meaning rescuing of guilt and not violence? I believe the issue for this comes from the understanding of “teshua” or “salvation.” Christianity’s focus on the removal of guilt to achieve salvation in the afterlife has shaped the way that we understand the language of the Bible, even if the passage is not addressing the issue of guilt.

In some ways, this all makes sense. In the psalm, the author, David, is asking for forgiveness after raping Bathsheba and having Uriah killed. However, there is a theological and focus shift at verse 13 from David’s guilt to his confidence in the assurance found in God. This verse falls into the second part of the psalm in which the author is reflecting on what it will mean to be restored to God.

In this light, rescue from blood(shed) and “salvation” is something that is restored (i.e. God’s protection is restored). It is not something that the author is looking towards for the afterlife, but hoping to have restored in this life.

Often, it is easier to place hope into the afterlife than to hope for change in this life. But the Bible is constantly urging us towards something more. Liberation in this life and the invitation to work with God to bring about liberation to all people.

This is where CPI puts our efforts. Not solely in the hope that there is something more, but in the hope that our subversive action in this life can make real change in the world.

We believe affirmation and recognition of systemic issues is not enough. Our calling, as those who seek to reflect the divine to the world, is to join in that work and fight against the oppressive nature of our world. God is the God of the oppressed, but that means God is the God of liberation.

– Kalie May

You can find out more about Kalie May here.

- Was Joseph Transgender? Historical and Literary Evidence for Understanding Joseph as a Gender-Expansive Person. - January 14, 2025

- Deconstructing and Leaving? Or Leading? - October 29, 2024

- The Myth of Moral Decline: Why we believe we are getting worse and how that can used to make us worse.The Myth of Moral Decline: - June 5, 2024